Tuesday, November 9, 2004

At 3:30 this afternoon four of us packed into a car and drove off to the outskirts of Modi'in, the site of the rapidly expanding new Buchman neighbourhood.

Turning off the main road towards a sign marked "No Entry: Work Vehicles Only", the little car bounced along a dirt road through a building site, eliciting quizzical looks from a few workmen before arriving at a pastoral hillside. The scars of the building work had already gashed one side of the valley, but the slopes ahead of us were still in their natural state. Bright red tapes marking two archaeological sites were easy to make out against the vegetation and stone.

It's a cliche here that everywhere you walk is an archaeological site from some period, but the Modi'in area is especially rich, with continuous human settlement going back at least 6000 years to the Chalcolithic period. We are lucky enough to have the dawn of modern human civilisation in our backyard.

On the ridge above us in the distance, giant drills and diggers were visible, their din breaking the pleasant stillness of the place. They warned of the fate awaiting these hillside archaeological sites, slated to be built over in the next phase of the construction project. This may have been our last chance to see them before they are destroyed.

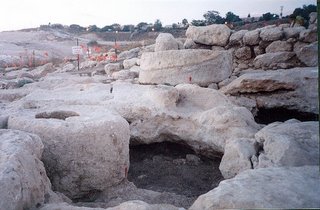

We tramped up to the first site, a field strewn with primitive flint tools, the kind we learnt about when we did a project on prehistoric man in school. This site was indeed Chalcolithic. The area is scattered with strange shallow dish shapes, gouged right out of the bedrock, flowing into each other to form some kind of complex.. The people who made this vast network didn't even have chisels - the rough marks of their flints are still visible.

The layout of the basins reminded me of a primitive olive press. The eastern Mediterranean is after all the cradle of the olive civilisation, the region where the olive tree was first domesticated.

Above some of the Chalcolithic remains are rough stone structures, dating from the Early Bronze period, a strange network of curved walls rather than a regular shape. In the centre is a circular

structure, perhaps the base of a tower. No one has quite worked out what this is yet, but a chill washed over me standing so close to something so ancient.

A short walk from there is a second excavation of a much more recent settlement from "only" about 2000 years ago. It dates from the Hasmonean period, the dynasty of priestly kings who made Modi'in famous as their home town and the scene of the Hannukah story.

This site is even more impressive, with more easily identifiable stone ruins. Though it is still millennia old it is much more familiar. Here archaeologists found coins, jugs, pottery - everyday objects familiar to modern people.

I was most struck by the mikve, a ritual bath which is at the centre of every religious Jewish community to this day. Unlike those I've seen at other archaeological sites, this one is generously sized with wide, boldly carved steps leading down to a vaulted room, traces of the original plaster still just visible on the walls. Next door is the cistern used to collect rainwater for the bath.

Other than a large fortlike structure above, though, there are no dwellings in the immediate vicinity, save possibly for some cave homes, still under excavation. Why the huge mikve then?

The answer seems to lie in the industrial olive oil press at the heart of the site. The grindstone alone must weigh several tonnes. The thought of carving and transporting such a

massive object without the aid of modern machinery is awe inspiring. The adjacent basin for collecting the oil is equally huge. Our guide noted that it is one of the largest found in the region, even though olive oil production was a major industry in ancient Israel and Judea, and large presses have been uncovered across the country, including several in and around Modi'in.

Modi'in is known to have been on the major ancient highway to Jerusalem. A hill close to my home in Modi'in is covered with over 100 water cisterns and several columbaria (dove cotes) - far more than would have been needed for a single town at that time. It also features a couple of large, though not as impressive, mikve baths. The site appears to have been some kind of pilgrims' rest stop where they prepared and purified themselves for the last leg of their journey, Modi'in being about a day's walk to ancient

Jerusalem.

The Mishnah, the ancient book of Jewish law, mentions that Modi'in is the first town along the route where pilgrims could buy earthenware for use in Temple rituals as it was close enough to Jerusalem that local potters kept themselves and their vessels in a permanent state of ritual purity.

It is possible that this giant olive oil press was also producing for the Temple, hence the adjacent mikve and bath, so that all those working the press could keep themselves ritually pure. Likewise this would explain stone utensils found at the site - according to Jewish law stone could not contract ritual defilement the way pottery could, and thus was often used for ritual purposes.

Could this site have belonged to the Temple or to Cohanim, priests who worked at the Temple? Could this have belonged to the Hasmonean monarchy, who were themselves priests? It would perhaps explain the fort guarding the site.

It is still early days and there are many questions to be answered. Artifacts from the site are still being dated to determine which part of the Hasmonean era they are from. Already one silver coin has been found from the late Hasmonean period. Other coins need to be cleaned and studied. The archaeological report on the site has yet to be issued.

Time is not on the side of the researchers though. As in many parts of Modi'in the Ministry of Housing and the powerful contractors who greatly influence development policy in Modi'in have brought pressure to bear on the Antiquities Authority, and, like so many other interesting sites in the town, this too is slated for a new housing

project.

Dr Ofra Auerbach, a local conservationist, has seen this story play out too many times. A resident of the neighbouring older town of Makkabim, now annexed to the Modi'in municipality, she has watched the new town of Modi'in swallow up the rocky hillsides on her doorstep.

She has seen countless emergency excavations, required by Israeli law before land can be developed. Several of these digs uncovered fascinating finds, including a Canaanite watchtower and a Hasmonean-era industrial zone and farmhouse, all of which were filled in and built over. Not far from the site she showed us today, one of the most ancient synagogues in the world was discovered, alongside a town square, a luxury villa and a row of alley houses. Only the synagogue and adjacent alley were preserved, and though protected by fencing, they are being rapidly hemmed in by roads and construction work, parts of the site already buried by the widening of a key Modi'in access road.

This time though, Dr Auerbach is determined to put a stop to the eradication of Modi'in's heritage. How can modern Modi'in, named for the ancient Modi'in of the Hasmoneans and the Hannukah story, be so blase about blotting out its own Hasmonean history? With all the parks in this town, surely some of the archaeological sites could be preserved, the town plan slightly altered to make room for historic Modi'in to find a place within the fast growing "city of the future"?

To date, her pleas, and those of fellow conservation campaigners have fallen on indifferent ears. Several members of the town council have taken up her cause and citizens are organising a petition to be sent to city

hall and the Antiquities Authority.

The growth of Modi'in may bring in more money for the contractors, but it also means more concerned citizens, shocked to discover that their homes were built over, rather than alongside, such rich archaeological sites. A savvy municipality could surely develop a thriving tourist industry around these finds which are of particular interest to Jews and Christians around the world.

We don't know if this story will have a happy ending. If once again the influential building lobby wins, at least some of the town's residents will be able to show their children photos and tell them the story of what was once here.

Residents of Modi'in are rooting for Ofra though, and her dream that generations of Modi'in school children will yet learn about olive oil making and the Hannukah story at this very site.

We certainly hope so.